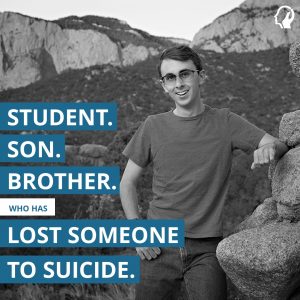

Anton’s Story

The biggest and most straightforward thing we can do is tell ourselves, our friends, our families, our human race that not being okay is okay.

Anton Q. Pieniazek

Lost a Loved One to Suicide

We don’t expect a lot of things to happen to us. I didn’t expect my father to kill himself. I expected Friday, December 6th, 2019, to be any typical teenager’s day, a day filled with procrastination, a lack of sleep, and good times with friends. And it was. Until I finally got home.

It was 1:37 p.m. when I noticed that I had five missed calls from my mom. Scared out of my mind, I called her. She sounded panicked, worried, and undoubtedly frustrated. She said I needed to get home, and that my older brother would pick me up. When we arrived home, my mother told us what had happened. My father had passed.

In 2017, the average suicide rate in America was 14 per 100,000 individuals, totaling around 1,078,000 suicides,  making suicide the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S. This statistic is only growing, and I’m not the only one who can speak from experience to tell you it’s a problem. There are around 7,000 to 12,000 kids every year (580-1,000 monthly) in bereavement because a parent died by suicide. Last year, me and my little brother were two of those kids. We’re not the only ones who can tell you that it sucks losing a parent. Period. Some would consider it is arguably worse when it’s due to suicide.

making suicide the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S. This statistic is only growing, and I’m not the only one who can speak from experience to tell you it’s a problem. There are around 7,000 to 12,000 kids every year (580-1,000 monthly) in bereavement because a parent died by suicide. Last year, me and my little brother were two of those kids. We’re not the only ones who can tell you that it sucks losing a parent. Period. Some would consider it is arguably worse when it’s due to suicide.

My father was diagnosed with depression in the months leading up to his death. Mental Health Disorders such as Depression, Anxiety, PTSD, eating disorders, personality disorders, and trauma disorders, can lead to this terrible act of desperation. And all of this can be hidden and not apparent to us. I knew my father had depression, and I knew of a traumatic incident he had when he was younger. But I didn’t see it play into his day-to-day. It just wasn’t evident.

According to a Johns Hopkins Medicine publication on suicide, “Losing a parent to suicide makes children more likely to die by suicide.” Suicide can also cause symptoms of PTSD of the person who killed themselves, according to Harvard Medicine. Suicide survivors (friends and family of the person who died) can quickly become emotional after being reminded of them in so many ways, ranging from hearing their name to seeing their ashes or the body of that person. This makes suicide, in some sense, an epidemic. So why aren’t we doing anything about it?

There is a stigma around suicide. People can and often do view it as selfish, cowardly, and many other different things that are just not true. Often, as John Nieuwenburg speaks in his TEDxStanleyPark talk, people want a way out of the pain they are feeling. They may not want to leave. They feel the need to leave, to better serve their friends and families in some sense because they think that they’re a burden to others. These are the facts, not the myth that we repeatedly hear that perpetuates that people die by suicide because they want to die. That may be true to some degree, but realistically, people want to end their suffering, and when they’re in that dark part of town, they don’t see any other avenues to take.

So what do we do to combat this? What do we need to do to change the stigma around suicide? It’s about parents telling their kids what suicide is and the fact that it’s becoming more and more of an epidemic. It’s about teachers explaining to their students what suicide is, the warning signs of it, and what to do when you see them.

The biggest and most straightforward thing we can do is tell ourselves, our friends, our families, our human race that not being okay is okay.

If you or someone you know is feeling suicidal, please call 1 (800) 273–8255. Are you interested in sharing your story with The Quell Foundation? Email liftthemask@thequellfoundation.org to learn more.

Back to stories